What is LCA? How can it help us redesign our production systems?

Written by: Beatrice Bos

Edited by: Lalla Masondo

Which materials make a product more durable? How can I reduce the environmental impact of my product? In a world increasingly impacted by climate change and pollution, these are questions that some producers are starting to ask themselves. When trying to make any product more environmentally sustainable, looking to reduce carbon footprint and overall impact is key. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is “a method for the environmental assessment of products and services, covering their life cycle from raw material extraction to waste treatment.” (Muralikrishna and Manickam, 2022), which can help companies achieve this goal.

What is Life Cycle Assessment?

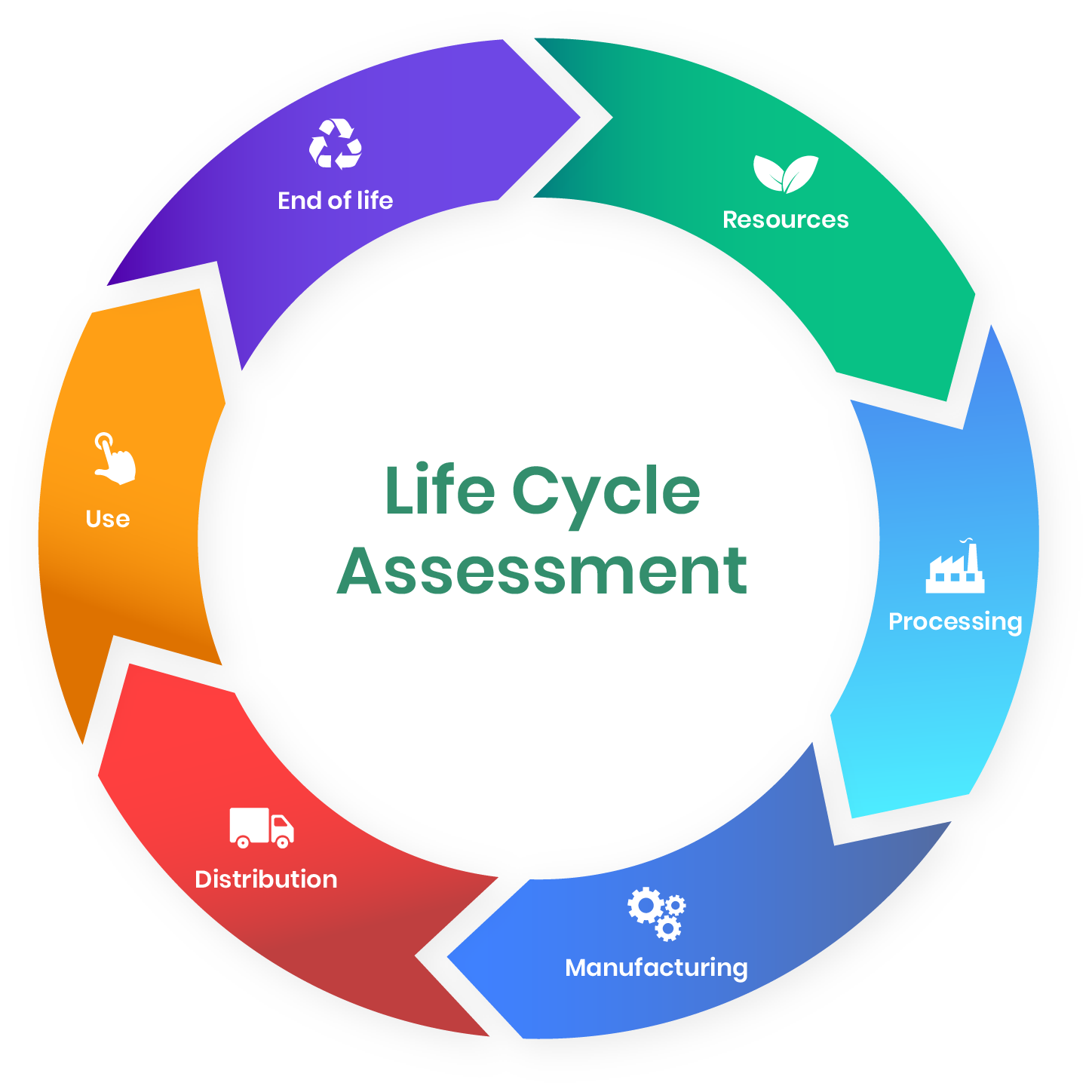

During LCA, the aim is to consider the impact of the product during its “life-cycle”. Assessing the life-cycle means analyzing the following phases of a product’s life: natural resource extraction, material production, manufacturing processes, distribution, use phase, and end-of-life, which is the waste treatment after the product is no longer usable. Sometimes, companies can also be interested in a specific part of the life-cycle only, such as the impact of the production phase (raw material extraction and manufacturing) or the impact of waste treatment. The objective is to look into how resources are being used in order to identify areas in which carbon footprint can be minimized and opt for reusing materials and consuming less energy (Gheewala, 2020). These are all steps that go in the direction of making products more sustainable; LCA acts as a tool to determine them and can help guide companies’ decisions.

The framework for conducting LCA outlines four essential phases: goal and scope definition, life-cycle inventory (LCI), life-cycle impact assessment (LCIA) and interpretation (Meer, “Life Cycle Assessment Goal and Scope Definition", Maastricht University, 2025):

Goal and scope definition:

The goal of an LCA should consider the reason why the study is carried out, what information the study can provide, and to whom this information is useful

The scope describes the detail and depth of the study, making sure to define what parts of the life-cycle are being studied, what assumptions are made or what limitations (for example, regarding availability of accurate data) could influence the study, and most importantly defining a functional unit and reference flow (Carbonbright.co, 2025). The functional unit is a quantified measure of the function of a product or service that is being taken into consideration (Sustainability Directory, 2025). Basically, it tells you what the company wants to use the product for, and this is fundamental for making more sustainable decisions. The latter, the reference flow, depends on the functional unit and it represents the amount of resources needed to achieve such function (Consequential LCA, 2015). During this phase system boundaries are also defined. This key step can be quite complex and this blog won’t dive into the specific details, but it is essential to acknowledge that system boundaries are an extremely important part of LCA.

Inventory analysis: Once the scope is defined, it is essential to identify the resources and processes which are part of the different life stages of a product. This is achieved by identifying all the input and output flows of resources (www.sciencedirect.com, n.d.) involved in the life cycle of the product, or the phase taken into consideration. While the reference flow represents the amount of resources needed to get to the functional unit, the inventory analysis looks at every little step to get to those resources. For example, the reference flow when the functional unit is a bag made of a certain material would be the amount of material needed to make the bag. The inventory analysis for the LCA of the bag would look at all the materials and processes needed to get the amount of material specified by the reference flow.

Impact assessment: After creating an inventory of all input and outputs of a system used to generate a product or service, the impact of these processes must be assessed. The way that this is done is by identifying all the different categories in which there is an environmental impact, and quantifying a measure of the impact in each of these categories. Many different methodology approaches can be used. There are specific strategies and parameters to do so, for example, for quantifying the long-lasting impact of emissions over different time frames. This is particularly useful because companies might be specifically interested in reducing impact in one area, for example their carbon footprint, but be less concerned with other factors, such as the land use needed to create the product (www.sciencedirect.com, n.d.).

Interpretation: This part occurs when you’ve finished the study. LCA can be quite tricky because a lot depends on how you gather data (and how much is available), what resources you consider, how you assign impact categories, and much more. As a result of this, there needs to be space to discuss the results obtained, underline variables and uncertainty, contextualize the results of the study, and make suggestions on decision-making (Hauschild et al., 2018).

Yogurt bottles: applying LCA

The Sustainability of Chemicals and Materials group at Maastricht University works on performing sustainability assessments of different materials to provide metrics and methodology on how to make materials more sustainable, also ensuring that when switching to more sustainable alternatives, impacts aren’t shifted elsewhere. The following hypothetical study included in classroom resources developed by the group can help grasp the main concepts of LCA, by providing a simplified situation.

The university serves yogurt in different packaging options. In an effort to reduce the university’s carbon footprint, the group aims to figure out which packaging option has the least overall carbon footprint in order to switch to serving exclusively that option.

It is specified that the university restaurant needs to sell 500 litres of yogurt per week. In this scenario, that’s the function that the product needs to carry out, so this would be the functional unit. To carry out this function, we look at the different packaging options. If there is one bottle that carries 200 ml of yogurt we need 2500 bottles to carry the functional unit. If there is another that carries 1000 ml of yogurt, we would need exactly 500 per week. These would be the reference flows for each option. It’s also important to consider what part of the life cycle we care about assessing. We assume that Maastricht University isn’t responsible for waste management, which gets handled by the local municipality; the university is only interested in assessing impact in the production phase of the bottles, because that way they can choose to order the option that generates the least emissions in this part of the life-cycle.

The bottles are made from different types of materials. During the inventory analysis, researchers look at all the resources that go into making the bottles. During this phase the goal is to identify all the resource flows, from inputs to outputs. If material production for a bottle results in emissions, these should be considered, depending on the goal and scope of the study. Flow of resources isn’t restricted to just materials, but looks at everything that is consumed and generated throughout the life cycle process. The inventory analysis allows researchers to understand what processes must be considered to assess impact correctly. During the impact assessment this is then quantified with different methods which we will not cover in this blog.

As can be seen even from this simple example, during LCA researchers must make several decisions on what to include in the study and it’s extremely difficult to see the full picture. For example, by considering only the production phase of the bottle, Maastricht University might decide to go with one option, but a study tracking the full life-cycle of those two bottle options might reveal that because of emissions in the waste-management phase, the chosen bottle was actually the least sustainable option. Also, the university is interested in carbon footprint and may overlook other impacts in the impact assessment section. These observations and specifications all must be included in the interpretation of results.

So what can we do with LCA?

The discussion presented above highlights some of the benefits and setbacks of life-cycle assessment. This method can be extremely useful in helping producers make more sustainable decisions, but it can also be challenging to define the strategy with which to conduct the study in order to get the most accurate results. Despite this, working towards refining or creating new methodologies for sustainability assessments of this type is decisive. In this context LCA becomes an extremely valuable tool that can offer helpful insight, but also a tool which we need to continue developing in order to overcome the different barriers that come with it. As current production systems face the obstacle of adapting to the need of sustainability, having standard methodologies that guide decision-making is crucial to paving the path to redesigning production systems that support the planet’s health: we must continue practicing and developing techniques like LCA.

For more information regarding these topics, consult:

US EPA (2015). Sustainable Materials Management Basics | US EPA. [online] US EPA. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/smm/sustainable-materials-management-basics.

Muralikrishna, I. and Manickam, V. (2022). Life Cycle Assessment - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [online] Sciencedirect.com. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/life-cycle-assessment.

Gheewala, S.H. (2020). Life Cycle Thinking for Sustainable Consumption and Production towards a Circular Economy. E3S Web of Conferences, 202, p.01003. doi: https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202020201003.

Carbonbright.co. (2025). Life Cycle Assessment: The 4 Stages. [online] Available at: https://www.carbonbright.co/insight/lca-life-cycle-assessment-the-4-stages.

Sustainability Directory (2025). What Is a Functional Unit and Why Is It Important in an LCA? → Learn. [online] Product → Sustainability Directory. Available at: https://product.sustainability-directory.com/learn/what-is-a-functional-unit-and-why-is-it-important-in-an-lca/ [Accessed 6 Jan. 2026].

Consequential LCA. (2015). Determining reference flows - Consequential LCA. [online] Available at: https://consequential-lca.org/clca/the-functional-unit/determining-reference-flows/.

www.sciencedirect.com. (n.d.). Life Cycle Inventory Analysis - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/life-cycle-inventory-analysis.

www.sciencedirect.com. (n.d.). Life Cycle Impact Assessment - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/life-cycle-impact-assessment.

www.sciencedirect.com. (n.d.). Life Cycle Interpretation - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/life-cycle-interpretation.